I’ve have been meaning to write about this since I saw this article in the Guardian a few weeks ago, on response of Galapagos warblers to traffic noise. Having done a PhD on the impact of anthropogenic noise on birdsong, I do still take an interest in how noise affects birds generally. And, intuitively, it’s surely not surprising that birds are more aggressive in the presence of traffic noise – they are probably stressed by high levels of background noise in a similar way that humans are.

However, what tickled me what this finding:

“across the board, males slightly increased the minimum frequencies of their songs when traffic sounds were played – possibly to make it easier for others to hear them. And, while an increase in peak frequency was only seen in males that lived away from traffic, the team suggests that could be because the birds that lived near roads were already singing at the optimum peak frequency.”

Now, I don’t imagine most readers will be too struck by that kind of minute detail, but this was a central – and agonising – issue of my PhD. Do birds genuinely increase the frequency of their songs in the presence of (low-frequency) anthropogenic noise to evade its masking effect, in a similar way to how the shrill of car alarm can be clearly heard against the low frequency throb of traffic noise)??; or is the apparent increase in song frequency a result of singing louder, and thereby singing more shrilly??

In other words, is the increase in song frequency a first consequence, and therefore, implicitly, a chosen response by the singer; or is it an involuntary effect of the birds simply singing more loudly.

Believe me, that was some argument. A lot of it centred around the technical difficulties of measuring increased song amplitude in the field. As a result, in the one camp, there was Slabbekoorn & den Boer Visser (2006) providing compelling evidence for the higher minimum frequency of songs in urban areas, compared with rural areas. On the other hand, there were folks like Nemeth and Brumm et al arguing that said frequency changes were a by-product of other changes in singing response to noise (ie, singing more loudly), rather than a primary response in and of themselves. The argument got testy at times: ” … for crying out loud: singing higher may also matter!” ended the last line of this paper by Slabbekoorn, Yang and Halfwerk.

Little wonder that, in the middle of all this, I felt like the whole premise of my PhD was on quicksand.

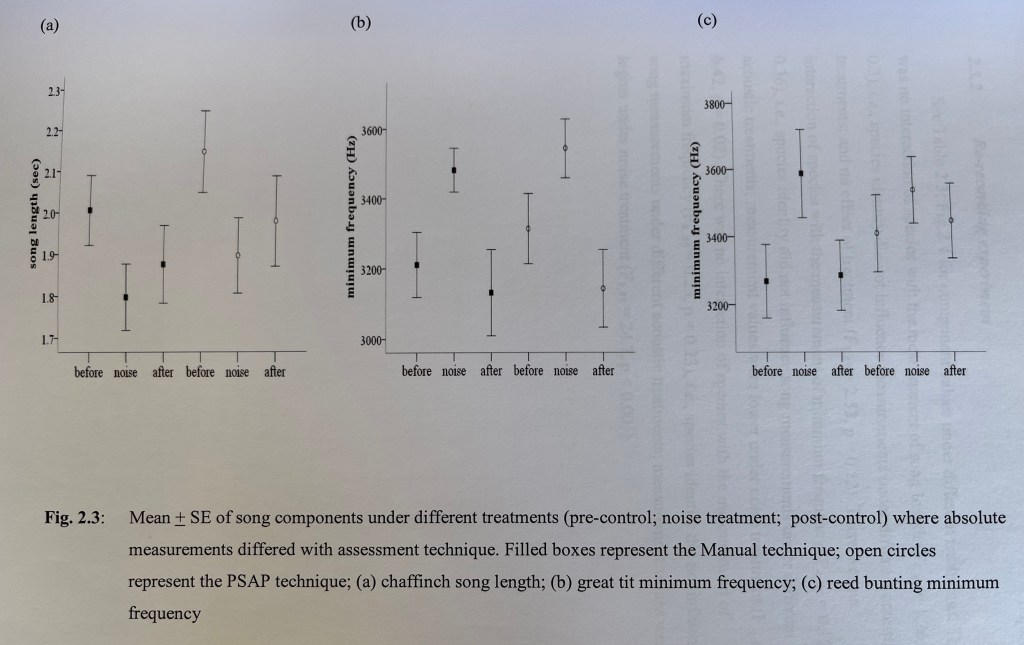

There was also the difficulty with the experimental treatment that I subjected my wild birds to, namely, exposing them to pre-recorded traffic noise and measuring any behavioural changes to their song. Because the noise treatment showed up on the recording, it was difficult to effectively adjust was called the “power spectrum automatic parameter tool” (Glory be, all the lingo is coming back to me!) of the software to measure things without human input. So essentially, I had to use the tool manually, in other words, subjectively. The image below illustrates the problem:

You can see how close the lower parts of the song is to the background noise level on the image on the right. The software couldn’t always cope and had to be constantly reset in an extremely time-consuming way. But arguably – and I do – my human vision could.

The reason I argue this is that, using a similar validation experiment to this paper by Verzijden et al (2010), I carried out a re-recording experiment on a number of species song-recordings with different singing styles (chaffinch; great tit; reed bunting), to verify that the background noise did not significantly affect the accuracy of manual measurements compared with the software.

However, there’s no doubt, as you can see in the chiffchaff image above, that the minimum frequency, ie, the absolute lowest part of each note of the song, comes dangerously close to overlapping with the lower frequency background noise (that long dark smudge at the bottom of the graph; the white bit underneath is where I filtered out the lowest frequency noise of all to help the software to work a little better, and to make the whole thing easier for me to listen to). So, I also used an eraser tool to wipe out some of the background noise where it was interfering with the software’s measurement of song length. Again, I had precedent. I was guided by this paper, by Kamtaeja et al (2012), who did exactly the same thing. And if my vision could measure accurately along a vertical plane (ie, the song frequency), surely it could also accurately assess along the longitudinal plane as well? I also took precautions …

On top of all that, and this is finally bringing me back to those Galapagos warblers, that set me off on this trip, I also measured the peak frequency of the lowest song syllable. At that time (and forgive me, I’ve been a bit out of touch in the decade since) peak frequency was not always measured when checking for the impact on the song frequency, at least not in most of the literature that I scoured. Researchers tended to stick with the lowest frequency. However, the advantage of peak frequency was that it was entirely measured by the software, there was no potentially contaminating effect of my human gaze. I included the peak frequency measurement to back up whatever findings might emerge for the impact of the traffic noise on the lowest frequency part of the song.

Ok, I know, to the unfamiliar reader, what’s the big deal? Well, lowest frequency is the absolute lowest part of the song; peak frequency is the dominant frequency of the particular sound, ie the loudest part. They aren’t quite the same thing, although they both give an assessment of what might be shifting frequency-wise in the low frequency part of the song in response to low frequency noise.

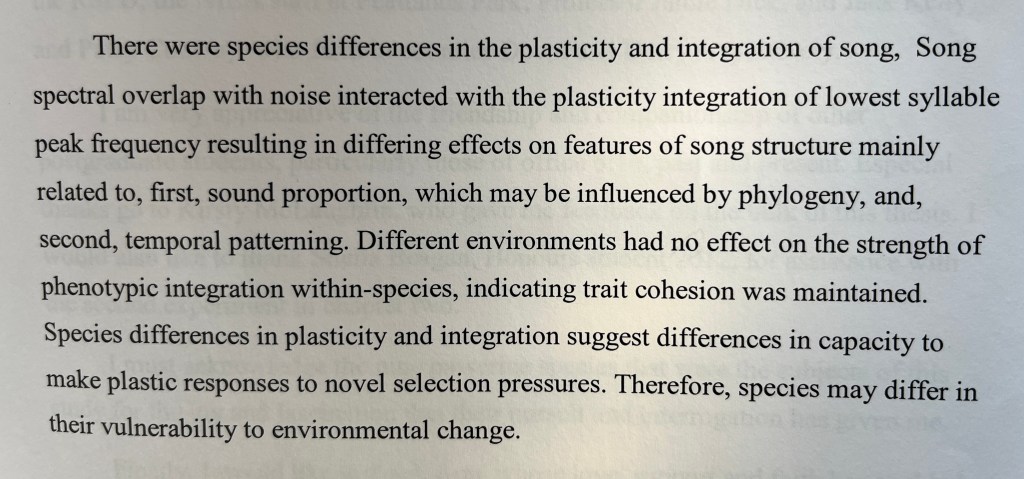

I’m so glad I did measure peak frequency. It turned out to be very important, and the wider implications were among the most important findings of my PhD. I essentially found that singing birds were happy enough to sacrifice the absolute lowest frequency part of their song; but peak frequency was more important. I linked this to what’s called plasticity integration – because the song changed in response to the noise, the birds integrated these changes in a way that maintained the cohesion of the song as a whole. But the foundation of that integration was its reliance on the peak frequency. Birds were probably unwilling to sacrifice the peak frequency too much, because across the animal kingdom, low frequency elements to a voice, particularly a male voice, are a sign of maturity. This was consistent across nine different species (chaffinch; wren; robin; blackbird; song thrush; great tit; reed bunting; chiffchaff; willow warbler).

So imagine my pleasure at reading that the research described in the Guardian article found that the birds living away from roads shifted their minimum frequency when experimentally exposed to it – corroborating the idea that the shift in frequency is a primary response (rather than merely a consequence of singing more loudly). The birds already living next to roads, on the other hand, did not change their peak frequency, probably because they “were already singing at optimum peak frequency.”

Maybe they had were already performing at maximum integration of their song in relation to that peak frequency difference as well?

These Galapagos findings feel like a confirmation that I was on the right track all along. Which is nice, because the immediate aftermath of my PhD was a bit of a rollercoaster. I wrote a paper, but unfortunately, I think I fell foul of the polarised argument that I’ve described above. Without belabouring the details this far on, that paper was sent out ultimately to five different reviewers for the one publication (2-3 is the norm, as I recall), before it was rejected. There were some scathing comments from one reviewer about my methodology. I’m guessing he was on the “other side”.

It was upsetting at the time. I had gone to so much trouble to validate my methodology (to the extent that it must have cost me about 4-6 months of my PhD). But I had already decided that the PhD was enough for me, I wasn’t going to pursue an academic research career at that stage of my life. I’d done pretty well to get the PhD as it was. And inevitably, as I then pursued other things instead, the possibility of scientific publications faded further out of reach. I simply had neither the time nor the inclination.

Ah well.

However, it is nice to see that the Galapagos warbler findings bear out some of my own. I guess now I’ll be on the look-out for anybody interested in seeing how peak frequency changes influence the overall integration of birdsong. But you’ve read it here folks, I got there first!